Joe Zidle: Seeing Through the War Clouds

With the war in Ukraine entering its second month, it seems clear that there’s no going back to a pre–February 24 world. I asked Andrew Dowler, Blackstone’s government relations expert in Europe, to offer his perspective on the geopolitical consequences. Andrew helps navigate political, legislative, and regulatory matters for the firm. I follow his policy views with my assessment of the evolving economic and market implications. Our hearts remain with all those in Ukraine.

Cold War II

by Andrew Dowler, Managing Director of Government Relations for Blackstone in Europe

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the political consensus was that Vladimir Putin was all “jaw jaw” rather than “war war”. Many argued that for him to enter a war he could never win, with or without huge suffering on his own side, would be wholly illogical. US and UK military intelligence said differently but were ignored. The West’s 20-year policy of giving Putin the benefit of the doubt held, paving the way for the greatest failure of European political due diligence since the Russian tanks rolled into Hungary in 1956.

Dissenting voices had long argued that Putin’s risk appetite was different. They didn’t need hindsight to know that his annexation of Crimea was a clear sign of a gambler with a penchant for recklessness. And they didn’t need it when he invaded Chechnya and Georgia, used polonium in a London hotel, downed a passenger airline, and used chemical weapons in Syria and on the streets of Salisbury in the West of England.

Despite all this, ideologically right-wing and left-wing extremists gave him comfort. And the mainstream forgot the traditional doctrine of deterrence and made a naïve foreign policy mistake.

A new geopolitical landscape At the time of this writing, the military implications are unclear and publishing deadlines would likely render hollow any forecasts. Whatever military scenario plays out, this war will fundamentally change the world’s geopolitical landscape.

Cold War II looms. A new wall may not be built, but seeing a Europe that is not sharply divided between West and East again is difficult. In Russia, future living standards look as grey as they did during Cold War I, with a depression following a 30% contraction in GDP and hyperinflation.

The impacts in Western Europe will be different. For one, NATO, perhaps with Finland and Sweden as new members, will be strengthened, as the threat from Putin is finally clear to all. Helping the cause will be a US recommitted to international defense and the Atlantic Alliance.

In addition, the EU has been remarkably emboldened since the invasion, quickly discovering the need for rearmament and the benefits of strategic autonomy and self-sufficiency. It will now surely grasp the opportunity to become a defense union and superpower in its own right, taking its place alongside the US and China in international affairs. That opportunity has been made possible by Germany’s policy volt-face after a decade of Russian appeasement to full and active military involvement. Chancellor Olaf Scholz has promised to increase German defense spending to 2% of GDP and to invest a one-off sum of €100 billion, twice the country’s annual defense budget.

Critical to the EU’s rise is Emmanuel Macron, now the de facto leader of Europe. He will now be re-elected easily as president of France. (His main opponent, Marine Le Pen, had to pulp her election brochures, as they included a picture of her shaking hands with Putin.)

Energy crisis to strain wallets, democracies Energy prices, soaring as a result of an oil and gas supply crisis complicated by perhaps ten million displaced Ukrainians entering Western Europe, will put severe strains on less temperate democracies than France and Germany. Expect that extremists attempt to exploit shakier democracies, but fail. Their tacit support for Putin has undermined them, and the politics of war has strengthened the case for internationalism and underlined the dangers of nationalism.

The cost-of-living increases will hurt, particularly in the UK. Russian gas represents just 5% of UK supply, compared to 50% in Germany and Italy and almost 100% in Finland and Latvia. But while the Brits may get most of their gas from the North Sea and Norway, they’re sold on the open market. With UK gas storage capacity now minimal, the UK depends on fluctuations in prices, which will remain high as Europe turns away from Russian supply. There could be a real political impact from the combination of diminishing disposable income and Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s limited ability to offer tax cuts and other economic sweeteners.

Russia, an uncertain future Many expect the invasion of Ukraine to bring about fundamental change in Russia, but it took 12 years for the USSR to collapse after its invasion of Afghanistan. The fear is that the rest of the decade will be spent arguing about war reparations and whether to seize Russian Central Bank assets to pay for them. We can certainly expect a war crimes investigation that lasts for many years. And if Putin remains in power for that process, it will poison Russian relations with the West for that much longer.

Managing the Headwinds

by Joe Zidle, Senior Managing Director and Chief Investment Strategist, Private Wealth Solutions

As Andrew argues, the world order is shifting. The economic cost of this war will extend well past the end of hostilities, no matter when peace comes or what shape it takes. The consensus view is quickly becoming that Europe will enter a recession this year. While the risk of recession is certainly elevated, I expect that COVID-era fiscal and monetary policy tools will be applied to backstop economic growth and subsidize households impacted by record-high inflationary pressures. This will help to mitigate the worst-case economic scenario and could allow for a soft landing for the European economy. Also, one should separate the business cycle from the economic cycle. The likely scenario is a more challenging environment for markets vis-à-vis lower corporate profits and wider credit spreads in Europe, the UK, and globally.

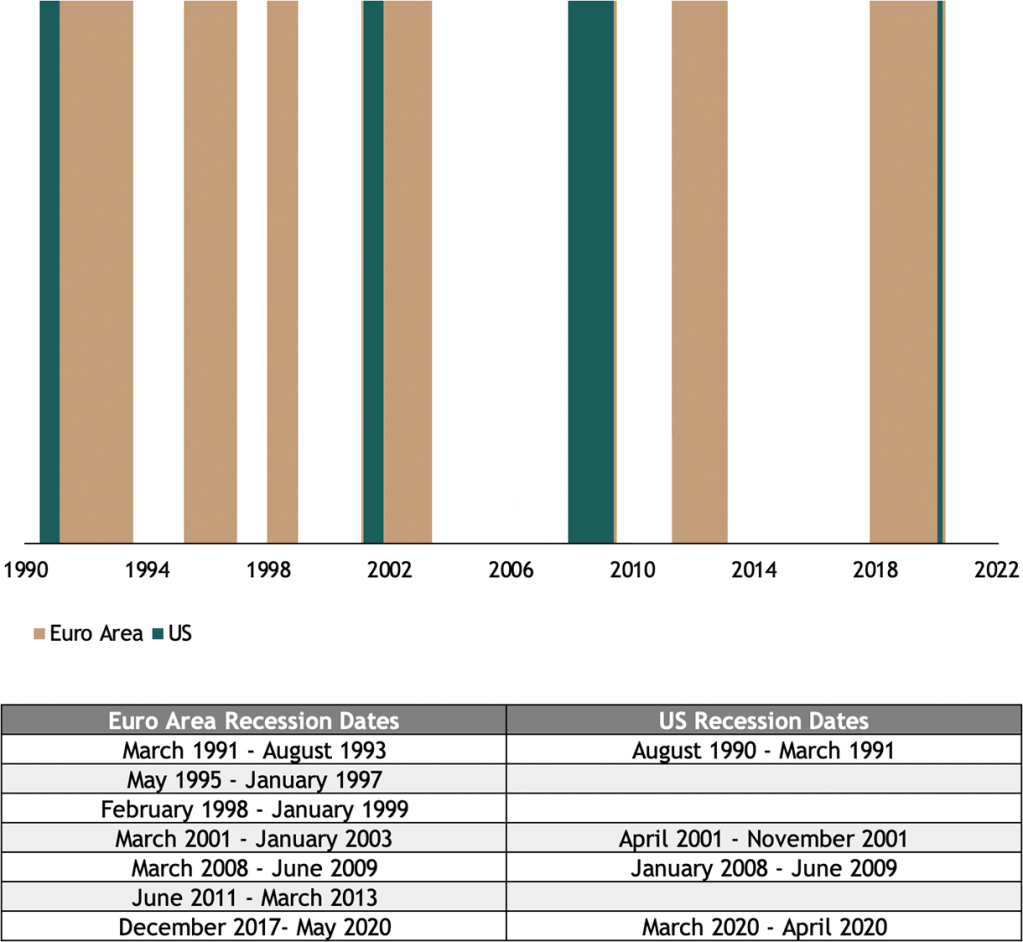

COVID-era policy solutions reduce recession risk If the war in Ukraine happened in a pre-COVID world, I would have been skeptical about the EU deploying policy solutions in time to avoid a recession. Back then, the Eurozone’s fiscal policy was rigid, bordering on austere, especially when it was needed most. It almost always focused on spending and debt levels between relatively stronger northern European countries and the shakier fiscal accounts of southern European countries. The European Central Bank (ECB) focused on inflation more than financial stability. Partly as a result, the Euro area had roughly twice the number of recessions over the past 30 years as the US.

Figure 1: Recessions in the Euro area and US

Source: OECD, NBER, and St. Louis Federal Reserve, as of 2/28/2022. Represents OECD-based recession indicators for the Euro area, and NBER-based recession indicators for the US.

Today, COVID-era policies offer Europe a lifeline, including more than €150 billion of untapped relief funds. In contrast to the US’ front-loaded response, EU spending continues to flow into the economy. Policymakers are already discussing another joint bond offering. And there is an alphabet soup of ready-made tools budgeted for in the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2021–2027.

The actual limits to borrowing and spending in a unified EU are untested. Debt as a percent of GDP was 97.7% in 3Q 2021 compared to 123% in the US and 250% in Japan. The sharp division in debt ratios between northern and southern Europe must be acknowledged. However, the EU’s COVID response showed that its members could agree to policies when the whole area faces a crisis.

Newly flexible ECB plus a growth cushion On monetary policy, the ECB will likely pivot to something less hawkish. Even in its recent announcements on balance sheet reduction and future interest rate hikes, it inserted language to allow for flexibility. The long end of the interest rate curve has room to move higher from deeply negative territory without meaningfully tightening financial conditions.

This war hit Europe at a time of relative economic strength. German unemployment was within 10 basis points of its pre-COVID lows, factory orders remained strong and leading economic indicators were positive. Growth forecasts for architectural and engineering services—a favorite leading economic indicator of mine—were strong for 2022. Europe’s recovery trailed the US’ by 6–12 months, so this year it was supposed to be Europe’s turn.

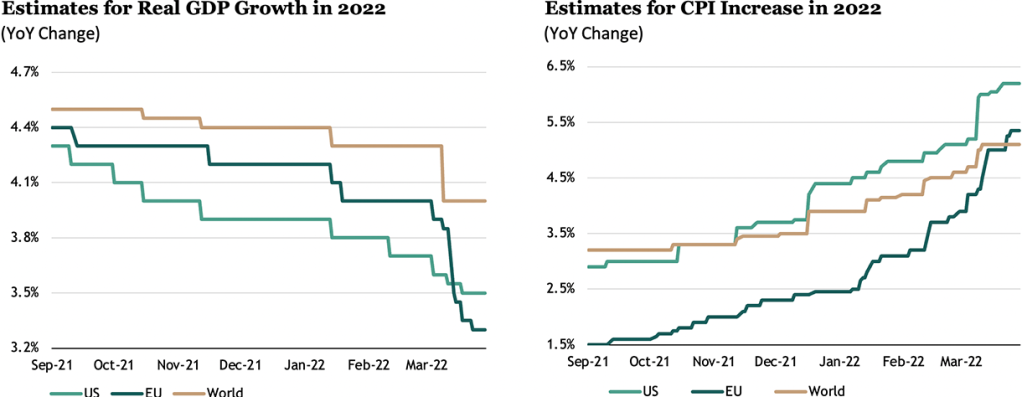

But the rebound will be cut short. The consensus growth estimate for 2022 fell to 3.5% in March from 4.2% in January and the forecast for 2023 is down to 2.1%. My own view is that forecasts will need to move still lower. Meanwhile, already-high inflation forecasts are now higher, and peak later, compared to the start of the year.

Figures 2 and 3

Source: Bloomberg, as of 3/29/2022. Represents median consensus economic forecast, as compiled by Bloomberg.

UK’s cushion smaller, but evident The post-COVID economic recovery in the UK has more closely resembled that of the US with a strong rebound in 2021, and as a result, the economy wasn’t forecasted to expand as quickly as Europe’s this year. Consensus forecast GDP growth has settled around 4% for 2022, before falling to around 1.8% next year. I am of the view that forecasts will be cut further. The UK will have to ramp up fiscal spending to subsidize consumers from the oil and gas shock, beyond what was announced in the Chancellor’s recent Spring Statement. Defense spending and other fiscal programs like utility rebates will play a critical role in supporting growth. The good news is that households still have excess savings, which should provide some cushion even as weaker consumer confidence and rising fears of job losses take hold.

Stocks Are Not the Economy

While I am optimistic that policy decisions can be made in Europe and the UK to prevent a near-term recession, the business cycle works at a different speed than the overall economy. Lower growth, higher inflation, and rising interest rates (i.e., the discount rate for stocks) present challenges for the markets, and I expect continued volatility, lower multiples and wider credit spreads to ensue.

There’s more to it than valuation Most major European indices are down roughly twice as much as US stocks, despite recovering sharply from early March lows. At 15x trailing 12-month earnings, the Euro Stoxx 50 is at recessionary valuation levels. But in my view, valuation alone is not enough to signal a buying opportunity.

Record high producer prices, such as the 25.9% year-over-year German PPI reading in February, will challenge companies’ ability to pass along cost increases. Higher interest rates in Europe and the US will also push up the discount rate for equities. Slowing activity is another headwind, as industrial activity, PMIs and global growth trends are hugely important to earnings of European companies, given their global exposures. Continued caution is warranted in my opinion. Higher-quality companies—those with consistent cash flow and less leverage—should provide a relative degree of safety for investors.

Selectivity required in fixed income European high yield markets are down nearly 5% this year, and the cost of insuring against EU high yield defaults moved to its highest level since the COVID outbreak. I expect this pressure to continue. As lower-rated credits struggle amid difficult operating conditions, sector selection will be critical. Higher-rated investment grade provides some cushion, though rising interest rates—driven by an aggressive Federal Reserve—may end up being the larger factor in returns. I expect shorter-duration fixed income, loans and other assets with the floating rate features to outperform, as a rising 10-year US Treasury yield lifts rates higher around the world.

Fundamentals Remain the North Star

This latest crisis can be expected to be a tipping point for major long-term structural shifts, ranging from globalization to the role of the US dollar in global financial markets. I plan to share my thoughts around these in the coming weeks and months.

For now, volatility is likely to continue as markets work through the war’s implications. The energy shocks are readily apparent; consumers see them at petrol stations and in their heating bills. But in periods of heightened risk, investors should look to the fundamentals as a guide. Currently, I see growth cushions in the EU and UK, and a newly unified Europe with policy solutions ready-made to support the economy. The path forward for investors will be more challenging as slower growth, higher inflation, and rising interest rates call for higher quality, greater selectivity, and a sharp focus on duration management.

With data and analysis by Taylor Becker.

The views expressed in this commentary are the personal views of Joseph Zidle and Andrew Dowler and do not necessarily reflect the views of Blackstone Inc. (together with its affiliates, “Blackstone”). The views expressed reflect the current views of Joseph Zidle and Andrew Dowler as of the date hereof, and neither Joseph Zidle, Andrew Dowler, or Blackstone undertake any responsibility to advise you of any changes in the views expressed herein.

Blackstone and others associated with it may have positions in and effect transactions in securities of companies mentioned or indirectly referenced in this commentary and may also perform or seek to perform services for those companies. Blackstone and others associated with it may also offer strategies to third parties for compensation within those asset classes mentioned or described in this commentary. Investment concepts mentioned in this commentary may be unsuitable for investors depending on their specific investment objectives and financial position.

Tax considerations, margin requirements, commissions and other transaction costs may significantly affect the economic consequences of any transaction concepts referenced in this commentary and should be reviewed carefully with one’s investment and tax advisors. All information in this commentary is believed to be reliable as of the date on which this commentary was issued, and has been obtained from public sources believed to be reliable. No representation or warranty, either express or implied, is provided in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein.

This commentary does not constitute an offer to sell any securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. This commentary discusses broad market, industry or sector trends, or other general economic, market or political conditions and has not been provided in a fiduciary capacity under ERISA and should not be construed as research, investment advice, or any investment recommendation. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.

For more information about how Blackstone collects, uses, stores and processes your personal information, please see our Privacy Policy here: www.blackstone.com/privacy. You have the right to object to receiving direct marketing from Blackstone at any time. Please click the link above to unsubscribe from this mailing list.