Joe Zidle: Transitioning from Policy to Fundamentals

My copy of John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money runs 403 pages but contains just two references to “animal spirits.” Even so, the concept is critical to understanding investor behavior. Keynes argued that “a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations.”1 In other words, many people would rather do something than nothing, even when they lack access to the full set of relevant information.

Keynes offered this take on animal spirits after experiencing the Roaring ’20s. His words will be especially important to keep in mind as the U.S. economy moves from estimates to evidence of recovery. As a result of today’s governmental largesse, households, corporations, and state and local governments are all poised to deploy historic levels of cash and the economy is set for a period of synchronized, rapid growth. But this growth will also be unpredictable, and the economy is already experiencing some growing pains. Stressed supply chains, labor shortages, and surging demand are exerting significant pressure on an economy that is still ramping up capacity.

In this month’s essay, we discuss why the early stage of this cycle will continue to be somewhat fickle, with heightened volatility in economic data and investor sentiment. We share our thoughts on how this cycle will unfold over the next 12 months. And then we outline capital allocation considerations as this liquidity-driven market transitions to a market driven by fundamentals under more challenging conditions.

A Return to “Normal” amid Uncertainty and Animal Spirits

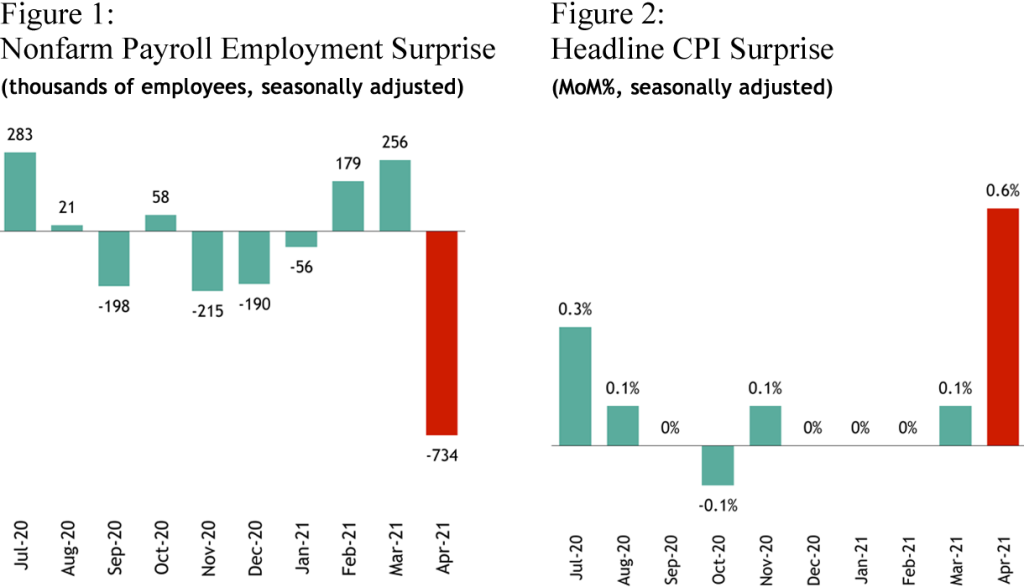

We continue to expect a robust recovery, but we don’t expect it to be completely free of bumps on the road. The flurry of recent economic data that missed forecasts by extremely wide margins was a prime example. These surprises highlight the difficulty in predicting how an economy responds to being jolted awake after such an unusual and uneven period of lethargy.

Bigger surprises a reality check The first release was the April jobs report, which undershot consensus expectations for the number of new jobs by a large 734,000 (see Figure 1).2 The Federal Reserve’s vice-chair, Richard Clarida, called it the “biggest miss in history.”3 Just days later, headline CPI accelerated by a head-turning 0.8% month-over-month in April, trouncing forecasts (see Figure 2). And then consumer sentiment plunged in May, coming in well below even the most pessimistic analyst’s forecasts.

Even if these reports are the only surprise data points of the recovery, which seems unlikely, the size of these misses has rattled investor and analyst expectations. Ultimately, imbalances will be worked out as prices adjust to solve for equilibrium between supply and demand. But in the meantime, we expect volatility to emerge from multiple corners of the macroeconomy.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Bloomberg, as of 5/7/21 (nonfarm payrolls) and 5/12/21 (CPI). “Surprise” reflects the difference between the initially published (i.e., non-revised) data point released by the BLS and the Bloomberg consensus forecast.

Fade the uncertainty, focus on what comes next Bumpiness in the data will likely continue to impact market behavior. As Keynes noted, animal spirits spur spontaneous urges to act rather than measured, quantitative analysis of likely outcomes. We think investors should fade the noise in the near term and focus on what the economy will look like after the initial months of this recovery.

To “Peak Growth” and Beyond

What goes up will come down this time. At some point in the next 12 months, we will pass the peak growth rate in just about everything. Historically high growth rates in fiscal spending, monetary accommodation, and private spending will give way to a lower, albeit more self-sustaining, expansion.

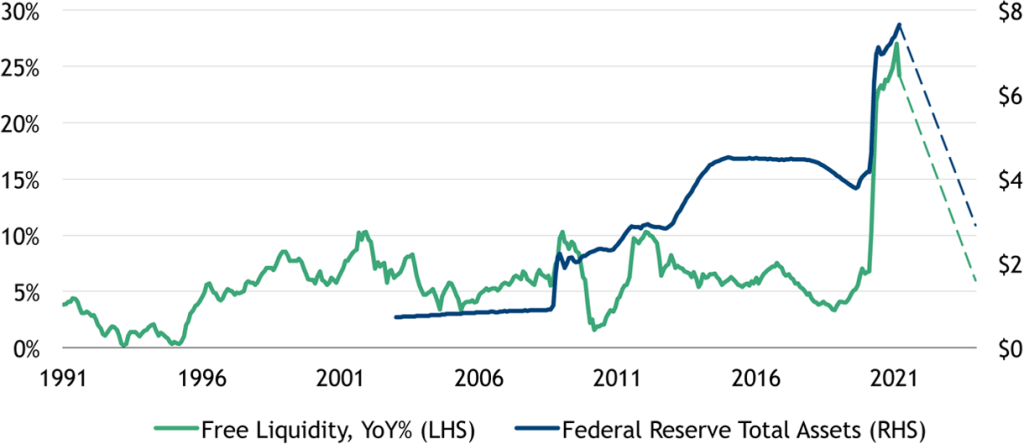

The next phase of monetary policy The size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet soared over the past year as the central bank resumed quantitative easing (QE). This support flooded the economy with cash, dramatically expanding the money supply. It also injected a massive amount of what I call “free liquidity,” which is the amount of money supply in excess of industrial production, one measure of output in the “real” economy (see Figure 3). But this type of growth can’t keep up forever. Monetary policy will eventually shift to a discussion (and ultimately, enactment) of asset-purchase tapering, followed by hikes in short-term interest rates.

Figure 3: Free Liquidity and Federal Reserve Assets

(US$ in millions)

Source: Federal Reserve and Blackstone Investment Strategy, as of 3/31/21. “Free liquidity” is defined as the difference between year-over-year growth in the M2 measure of the money supply minus year-over-year growth in industrial production (both seasonally adjusted). “Total assets” reflects the Fed’s total asset holdings less eliminations from consolidation and is not seasonally adjusted. Dashed lines illustrate each series’ return to its historical average over the time period shown.

The end of front-loaded fiscal policy The Biden administration has proposed over $4 trillion in fiscal spending with the American Jobs Plan (AJP) and American Families Plan (AFP), on top of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan passed in January. However, even if these bills were passed in their proposed form, which will be a challenge given the balance of power in Congress, it would take 8—10 years for the trillions in spending to be disbursed.

For example, the nature of infrastructure spending is such that even when capital is committed in a given year, actually getting it into the ground often takes much longer. As we’ve written previously, “shovel-ready” projects are often held up for years as they await approval. Even the most ambitious infrastructure package cannot deliver the same type of immediate stimulative boost as was delivered by the massive government transfers during the pandemic.

Savings and spending diverge Consumer savings and spending won’t climb in tandem forever, as they have in recent months (see Figure 4). We expect consumers to spend down some portion of their accumulated excess savings, which will temporarily boost consumption expenditure on goods and services. But even if the stock of savings remains elevated, the savings rate will likely return to more normal levels as confidence in the economy is restored. Additionally, the recent April data showed that the spikes in retail sales seen in May 2020 and January and March 2021 will be hard to repeat without the spending firepower of COVID stimulus payments.

Figure 4: Personal Consumption and Personal Savings

(US$ in trillions, seasonally adjusted annual rate)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of 3/31/21.

Liquidity giving way to fundamentals As the historic growth rates of liquidity and fiscal spending pass their peaks, fundamentals will drive market valuations and economic growth. This shift will usher in a slower-growth environment, but one that is “self-sustaining.” We define a self-sustaining economy as one in which consumer and business spending drive demand (not government spending), household incomes are derived from wages (not transfers), and interest rates reflect risk compensation and term premia (not ultra-dovish monetary policy).

Liftoff in 3…2…1… This type of self-sustaining liftoff didn’t happen during the U.S. economy’s recovery from the Global Financial Crisis. While the unemployment rate eventually fell to historically low levels, inflationary pressures never returned. As a result, the Fed took years to taper its QE program and the U.S. economy was seven years into the expansion before the Fed first hiked interest rates. Even then, the Fed had to walk back its rate hikes after just a couple of years, showing that the recovery never really took off without support.

Easy financial conditions and narrow credit spreads persisted and resulted in the longest bull market ever. This liquidity-driven, decade-long bull market was a comfortable environment for investors and firms alike, with plenty of capital to go around at low borrowing costs. Financial assets of all types posted above-average returns with Darwinian forces kept at bay. For perspective, the number of non- earning companies around the world set new records during the last cycle.

This time, the dry powder on consumer and corporate balance sheets all but ensures the economy achieves liftoff. The Fed will likely taper and achieve its goal of hiking interest rates much more quickly than in the previous cycle. And inflation will likely be sustained at a higher level than prior cycles.

The Next Phase: Fundamentals and Free Cash Flow

Higher prices and higher yields with less policy support will shift focus back to company fundamentals, putting at risk certain “beta” strategies that expect everything to perform well. This shift will leave fewer corners where underperformers can hide. Differentiation among companies will reemerge, as it will be challenging for businesses that have relied on cheap cost of capital to survive. But this new environment will also create pockets of opportunity for capital deployment.

Game plan for a changed investment landscape Discerning investors with high conviction in secular themes can benefit as they sift out the winners from the losers. Portfolio decisions made over the next 12 months shouldn’t be based on the last cycle’s assumptions of unlimited policy support, excess liquidity and permanently low interest rates. Because when the fundamental phase of the recovery takes hold, it will have implications across the economy and markets.

Higher interest rates, pushed up by inflation expectations and the withdrawal of Fed-sponsored QE, will mean a higher cost of capital for the average borrower. This change will impact firms’ ability to issue debt at ultra-low rates, especially those with weaker fundamentals. At the same time, higher input prices and wage costs will pressure profit margins for certain sectors, especially those with limited pricing power. S&P 500 profit margins set another record in 1Q’21, but the combined headwinds we have laid out mean that further margin expansion will be difficult to come by for many companies, especially those with limited pricing power.

Also, higher inflation will lead to further steepening of the yield curve in nominal and real terms. This steepening will push up discount rates on long-duration cash flows, denting returns for riskier firms that won’t return capital to investors for years. Speculative tech stocks, which plunged following April’s surprise CPI release, are a prime example. In contrast, sectors with strong current cash flows (like real estate) and positive exposure to higher-rate environments (like financials) could perform relatively well.

The rotation in leadership that results will likely cut across the growth vs. value debate, or technology vs. financials, more specifically. As a result, exposure to companies or assets within any sector capable of increasing free cash flow will be critical. In my view, an asset that provides growing cash flow at a reasonable price will outperform regardless of whether it’s considered new economy or old.

Uncertainty, but conviction My team and I are buckling up for the next few quarters, which could be almost as bumpy as our traffic-filled commutes. And that’s especially top-of-mind now that we’re happily returning to our New York offices. The coming months will bring considerable uncertainty to the outlook for market performance and economic data as the animal spirits Keynes defined make their way through the economy. However, we think that investors who keep faith in the strength of the coming recovery and shift their focus back to fundamentals can be rewarded for their patience and discernment.

With data and analysis by Taylor Becker.

- John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bloomberg, as of 5/7/21. Reflects the difference between the initially published (i.e., non-revised) nonfarm payroll employment number and the Bloomberg consensus forecast.

- Reuters, as of 5/12/21. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-clarida-idINKBN2CT1PE

The views expressed in this commentary are the personal views of Joe Zidle and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Blackstone Group Inc. (together with its affiliates, “Blackstone”). The views expressed reflect the current views of Joe Zidle as of the date hereof, and neither Joe Zidle, nor Blackstone undertake any responsibility to advise you of any changes in the views expressed herein.

Blackstone and others associated with it may have positions in and effect transactions in securities of companies mentioned or indirectly referenced in this commentary and may also perform or seek to perform services for those companies. Blackstone and others associated with it may also offer strategies to third parties for compensation within those asset classes mentioned or described in this commentary. Investment concepts mentioned in this commentary may be unsuitable for investors depending on their specific investment objectives and financial position.

Tax considerations, margin requirements, commissions and other transaction costs may significantly affect the economic consequences of any transaction concepts referenced in this commentary and should be reviewed carefully with one’s investment and tax advisors. All information in this commentary is believed to be reliable as of the date on which this commentary was issued, and has been obtained from public sources believed to be reliable. No representation or warranty, either express or implied, is provided in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein.

This commentary does not constitute an offer to sell any securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. This commentary discusses broad market, industry or sector trends, or other general economic, market or political conditions and has not been provided in a fiduciary capacity under ERISA and should not be construed as research, investment advice, or any investment recommendation. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.

For more information about how Blackstone collects, uses, stores and processes your personal information, please see our Privacy Policy here: www.blackstone.com/privacy.